- Boat

- Articles

- About

- Tehani-li Logs

- 2004

- Uligan Maldives

- Man, Oh Man, Oman

- Eritrea: The Nicest Place You’ve Never Heard Of

- Cruising Notes: Oman to Eritrea – From Pirates to Cappucinos

- Old Testament Sudan

- Egypt: Legend, Myth and Reality

- Thoughts on Cruising the Red Sea

- Greece: Civilization Again

- Montenegro

- Malta

- Sardinia, Italy

- Barcelona, Spain

- 2003

- 2002

- 2001

- 2004

- Contact

The Tuamotus: Beauty and Danger

A combination of sleep deprivation and lack of beaches for the little ones in which to safely splash helped make the decision to depart the Marquesas easier. We raised the anchor at Ua-Pou and then let the trade winds gently push us 500 miles west to our next family destination: The Dangerous Archipelago.

The Tuamotus were so labeled on old nautical charts to warn sailors the perils they faced if their ship should ever find itself trying to cross this particular swathe of ocean. From the water as an almost invisible string of low-lying islands and coral reefs through and around which flow strong unpredictable currents, “Dangerous” was an apt moniker and for centuries the islands have lived up to their fearsome reputation claiming hundreds of ships, lives and fortunes. Since they lie in a southeast to northwest line a couple of hundred miles wide and over 800 miles long straight across the most common route to Tahiti, they were a navigational minefield of unwelcome surprises to all oceanic traffic in the age before the miracle of GPS.

Navigation: the art of knowing where you are – even when you aren’t

Back in the day, ships used sextants, arcane mathematics and good luck to “estimate” their position. A very skilled navigator might be able to find his position and be accurate within a mile by measuring the angle of the sun over the horizon and keeping strict note of the exact time. Then he would have to use “dead reckoning” to estimate his speed and by watching his compass course would be able to have an idea of where he was later that night when there was no sun and he could not see anything. Note: this type of navigation is called “dead reckoning” for a good reason. Surrounded by sharp coral jaws and fierce ship-sucking currents sailing this area, if one was lucky, made for an uneasy couple of nights to say the least. We should also add that even today the islands are not all charted accurately in the South Pacific with some being up to two miles from “where they should be.” Brave men were needed for such voyages. Or idiots. But I prefer to go with the brave men theory.

For us the situation was much simplified. We know at a glance where we are and the GPS is accurate to within a few feet. We have electronic and paper charts and I keep well away from known obstacles especially at night. But even today ships, fishing vessels and cruising boats, are lost here due to hubris, carelessness or just all too common human error.

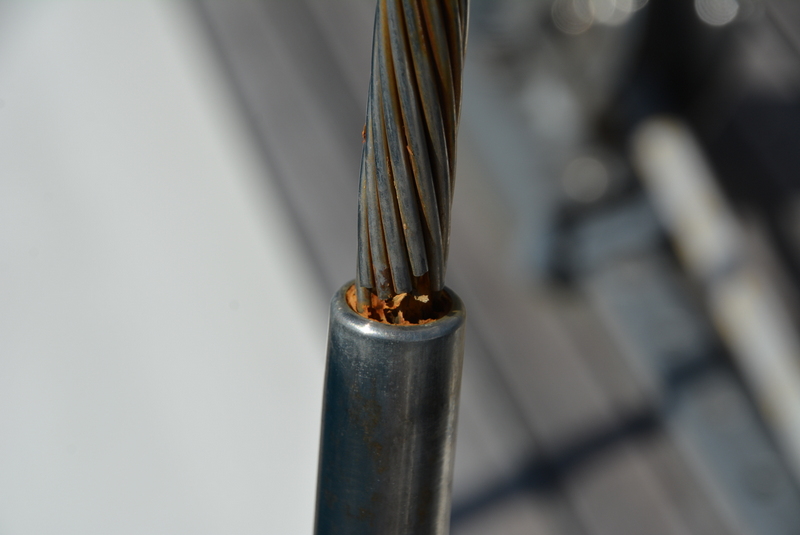

Our plan was to leave the Marquesas and sail to Makemo atoll in the Tuamotus, which is about half way down the chain. From there we could work our way north and then make the jump to Tahiti. Halfway across to our destination and just two days out of Ua-Pou, I noticed our lower shroud (one of the wires that keeps the mast from jumping out of the boat) looked a little rusty right at the swage fitting. I rubbed it with my thumb and was shocked to see metal pieces disintegrate and come off in my hand. Four wires had already been eaten through due to the silent cancer of crevice corrosion. A gust of wind heeled the boat over and then, “ping!”- a fifth wire broke. This was serious and called for a change in plans. We needed to head directly for Tahiti and replace this 14 mm wire (5/8 inch). I immediately reduced all sail and kept a careful eye on our new injury never letting speed exceed six knots.

As a great believer in preventative maintenance this latest setback was particularly annoying. Wire rigging on sailboats can last 15 to 20 years but should be changed every ten, particularly for offshore work. We had just, at great expense, replaced all of ours and at one of the best boatyards in Seattle. This should not have happened. But it did and we had to adjust. Makemo as a destination was out. We changed course for Tahiti and stopped at two of the Tuamotu atolls which lay now directly on our path.

Singing and Dancing

The atolls are giant rings of islands fronted by coral reef and from the air look like pearl necklaces scattered across the horizon. In the middle of each is a lagoon where often black pearls are farmed and sold in the towns. The girls were excited to visit the Tuamotus. They became even more excited when I read aloud to Ariel some cruising notes, “The Tuamotus have plenty of beaches but the shops have no veggies.” Asmara exclaimed, “Adriana! Beaches but NO vegetables!” They grabbed each other’s hands and began dancing and singing, “Beaches and no vegetables! Beaches and no vegetables!” All we needed now was free chocolate upon arrival and this would be kiddie paradise.

The atolls come in all sizes. Some are small and dangerous and others are large and dangerous, like Fakarava, which is 15 miles wide and 30 miles long with just two passes through which boats can enter. Negotiating a pass in a sailboat is a tricky procedure because all the water in an atoll has to leave and enter with each tide and the pass, sometimes no more than a hundred feet wide, is the natural choke point. Current inside passes can reach six knots or more depending on the state of the tide. Fighting a six knot current inside a narrow pass with razor sharp coral hungrily eyeing your boat on both sides is scary. Riding such a current in would be even scarier as the boat needs to go faster than the water to maintain steerage. The ideal time to enter or leave a pass is slack water: the period of time when there is no current.

One would think, quite rationally, that by using tide tables a sailor could time his entry or exit at the moment when current in the pass is at its least. And one would be wrong.

Not trying to be “slackers”

This has to do with several complicating factors. We are way off the beaten track and aside from nuclear testing (far down to the south of us), France has had no interest in these thinly populated, resource-free islands that are, frankly, a long way from Paris. Tide tables exist for only one or two of the many atolls and guesstimates are made for the rest. There is also the state of the wind the careful sailor must consider. Strong winds push water over the reef into the atoll and no matter what your tide table is telling you that water has to exit through the pass which can negate any tidal effect whatsoever. Coming from the Pacific Northwest where we have the second highest tides in the world (Cook Inlet, AK), we are familiar with these concepts and realize that “slack water,” the time between the out-going tide and the in-going tide can sometimes last an hour or it could only be a very short minute. And lastly, slack water is NOT low tide like many cruisers mistakenly believe. Often, depending on bathymetry and the shape of things unseen underwater, slack can be two hours or more either before or after low tide.

Therefore, our strategy, such as it was, was to “just go for it.” We have a largish boat and a 100 horse power engine. I figured I could not trust the tide tables programmed into my Navionics charts since I noticed they were the exact opposite of reality in the Marquesas. So we arrived when we arrived and left when we left. We stuck our noses in and made the decision whether to proceed or abort. This made for some exciting moments.

Our first atoll was Kauehi because it was on the rhumb line (or, “in the way” in sailor talk). Kauehi only has one pass which we approached with trepidation in the late morning after our 520 mile passage from the Marquesas. The weather was squally and as the passes are usually shallow you need to see the bottom to stay in deep water. Timing is everything as one must advance with the sun behind them not in front for the glare on the water obliterates your view. Wearing polarized sunglasses looks cool and helps here.

For us, the sun was high enough but there was an angry squall on the horizon and I could see it had evil intentions of coming our way. I wanted to get through the pass before it landed. Picking up the binoculars we could see no standing waves and proceeded forward. It was a piece of cake going in and we only had two knots of current against us. Right after making it unscathed through the pass the squall hit like Mike Tyson with horizontal rain literally blinding us so we just idled the engine and didn’t move while we watched the wind gauge show gusts of 35 to 45 knots. Since we were now in deeper water we were safe and it was time for lunch, which we ate as we sat through nature’s show. Like too much coffee, this passed quickly and we were soon on our way again. With Ariel on the bow as lookout, we motored carefully to the southeast corner of the atoll to anchor off a deserted palm tree-clad island that looked remarkably like the screen saver seen on so many desk-bound computers now (thankfully) far away. We spent a very pleasant quiet couple of days here swimming and beach combing. There were only two other boats with us which was a nice change from the crowded anchorages we have seen so far on this South Pacific journey.

Into the Witches Cauldron

The morning we left Kauehi the pass was boiling. The tide was moving out straight into six foot waves stirred up by strong trade winds which, that day only, were blowing a steady 25 to 30 knots. This was going to be a thrilling ride. Our over the ground speed began to pick up as we neared the pass and began to be sucked out. We could see whitewater and small standing waves. There were giant swirls on the surface as the water from the lagoon trying to get out met head on and fought with the water of the ocean trying to get in.

I stood at the helm and gunned the engine as our over the ground speed now hit 10 knots. Into the maelstrom we flew. We rushed up to a whirlpool big enough to swallow a Volkswagen spinning furiously. I dodged that. The water boiled up in front with foam and froth spreading out before us enough to cover a tennis court. I dodged that. A row of standing waves had now formed, three feet high throwing water in the air at the point of the waters collision. We smashed right into that. I told Ariel and the girls sitting there in the cockpit wearing lifejackets to hold on. My hands gripped the wheel and I bent my knees for the impact of the six-foot high waves just beyond. Wham! We hit. We were free.

Fakarava, Land Ho!

With 25 to 30 knots of wind behind us we moved quickly toward Fakarava, our next destination 50 miles away. Mindful of our weakened rig, I had reduced sail to the bare minimum. The swells were now reaching nine feet and we rolled up and over them one at a time as the miles flew beneath our blue keel. Hours later we spotted a thin row of green coconut trees seven and half miles before arriving. The girls began chanting, “Fakarava, Land Ho! Fakarava, Land Ho!” We were almost there. But we still had to negotiate the pass.

The north pass of Fakarava is half a mile wide: the widest pass in French Polynesia. The south pass is 500 feet wide, has a large coral island in the middle and narrows considerably after that. We were going to the south pass. This required turning the boat so the six to nine foot swells were now beam on, that is, hitting us sideways and severely rolling the vessel and its precious cargo. I waited until the last possible moment to do this and as we rounded up the swells beat into our hull and water flew across the boat from each impact. With the engine running strong we were soon inside the pass, again doing 10 knots riding the current. The wind was howling, the pass was narrowing, and the coral island in the middle was racing toward us. With one beady eye on the chart plotter and the other on the sharp coral fast approaching, I waited until the last moment and veered sharply to starboard to enter the narrow channel we needed.

They say at the pass there are several attractive bungalows, a restaurant and a couple of dive operations right on the water. I saw none of that.

We sped into the narrow channel which then opened up into the calm lagoon, one of the largest in the world. The wind eased, the swell had stopped and I might have even heard a bird sing. My fingers now welded to the metal wheel relaxed. Life began to return to normal.

After motoring five miles to the south eastern corner of the lagoon for maximum protection from the SE trades, we dropped the hook in 20 feet of water off Hirifa village. The “village” consisted of two houses and a beach bar run by the energetic and affable Liza and her hard working lean husband, both born a good while ago and raised in the Tuamotus.

That evening we had a big party with the half dozen other cruising boats there. One yacht, Liward from Kemah, Texas, with Steve and Lili on board had organized everything. Steve had brought his sound system and guitar and played for us a wide range of music including Jimmy Buffet, Van Morrison and even the Stones. He was quite good and encouraged a local lad on ukulele to join him. They took turns playing Tahitian music and American rock and roll the whole evening. Liza, a large woman whom, I would guess, has seen her way around a few microphones, kept running out of the kitchen to sing full-throated and sweaty every Tahitian song. As soon as the last verse left her lips she good-naturedly dashed back into the hot kitchen to keep the food cooking. We could not decide who was more entertaining and it was a nice, multi-cultural evening enjoyed by all.

July 9, 2015

5:05 am #comment-1

Kemah Texas….wow, your wife would like that place..it’s essentially a Vietnamese shrimp fishing colony. They had a few big shootouts with the local KKK chapter I believe. Needless to say the Viets prevailed. …wherever you go, that’s where you are……